Constraining the Baryon Acoustic Oscillation scale using the large-scale structure of the Universe

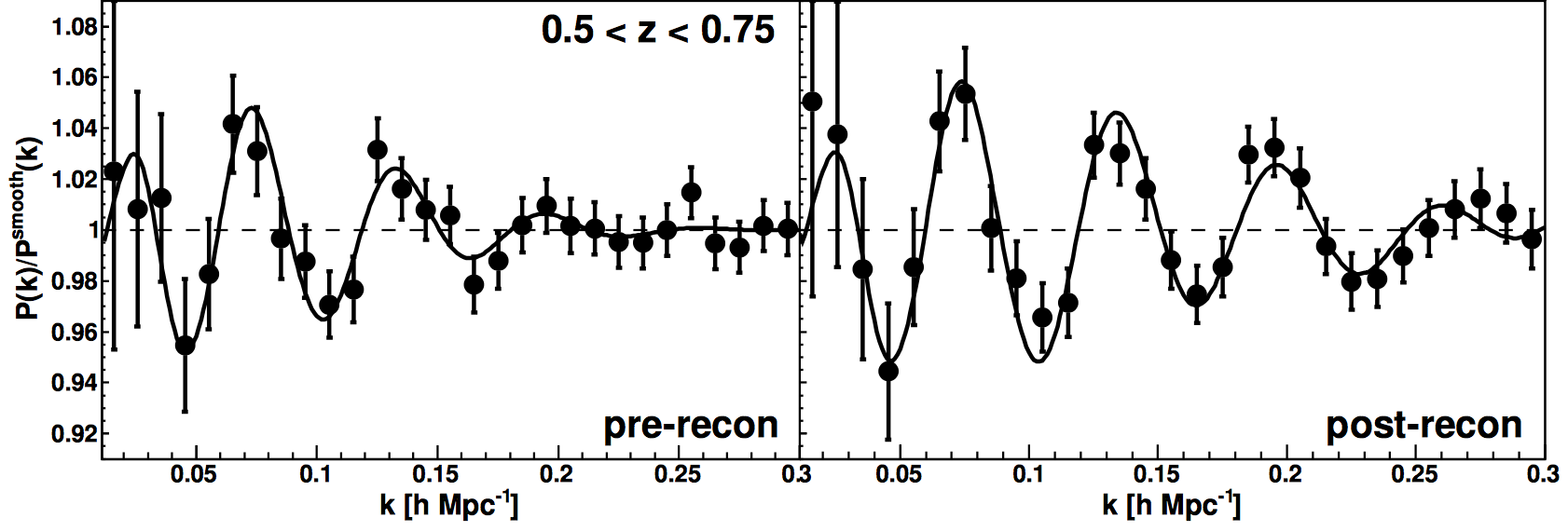

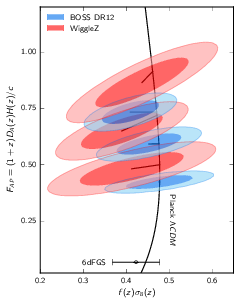

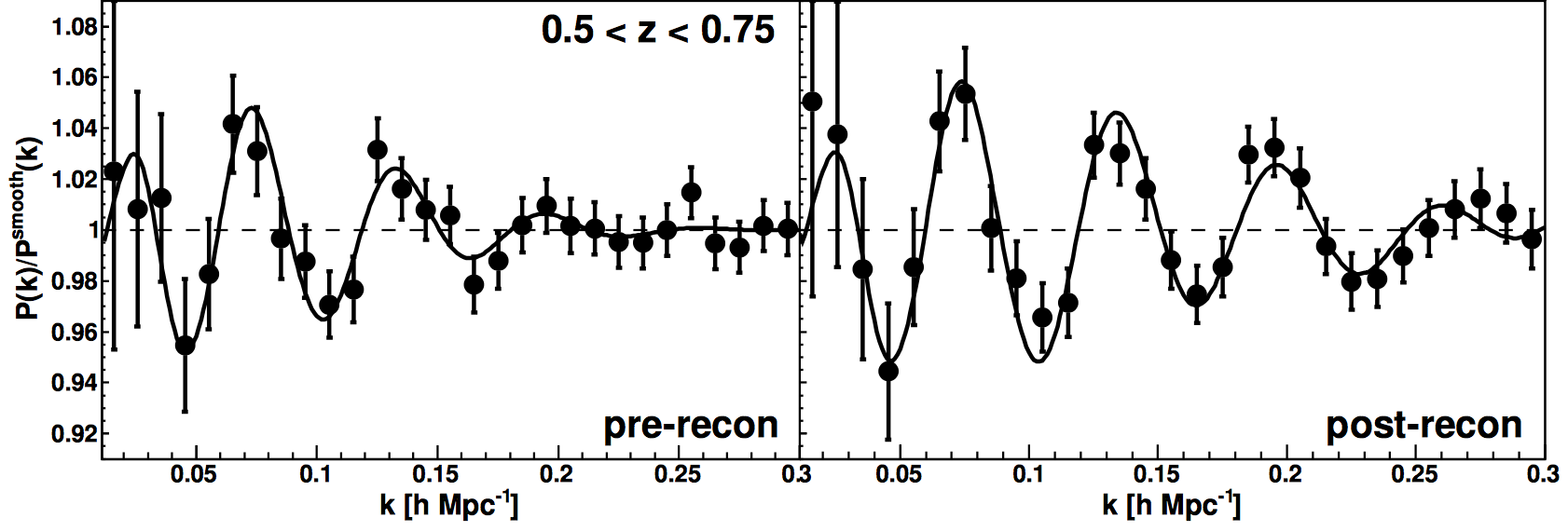

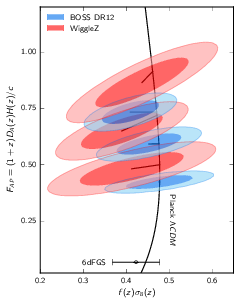

The Baryon Acoustic Oscillation (BAO) scale has emerged in the last decade as one of the most powerful tools to constrain

cosmological models. This scale has been imprinted in the matter distribution by sound waves traveling in the very early

Universe. We can use galaxy surveys to measure this scale, which allows to constrain the expansion history of the Universe.

The signal is located on very large scales, where perturbation

theory works quite reliably and therefore we have a very good theoretical understanding of this observable.

The good theoretical understanding of this signal means that even with current observational constraints of less than 1%, we are still

dominated by statistical, rather than systematic errors. This puts Baryon Acoustic Oscillations in a unique spot in cosmology and is

one reason why this observable is at the core of many future cosmological experiements. The study of potential systematic contributions

to this observable is a big part of my research and I am involved in the future

Euclid and DESI experiments, both of which

intend to improve current measurements by another order of magnitude in the coming years (further reading: Eisenstein et al. 2005;

Eisenstein, Seo, Sirko & Spergel 2007; Beutler et al. 2016;

Ding et al. 2017).

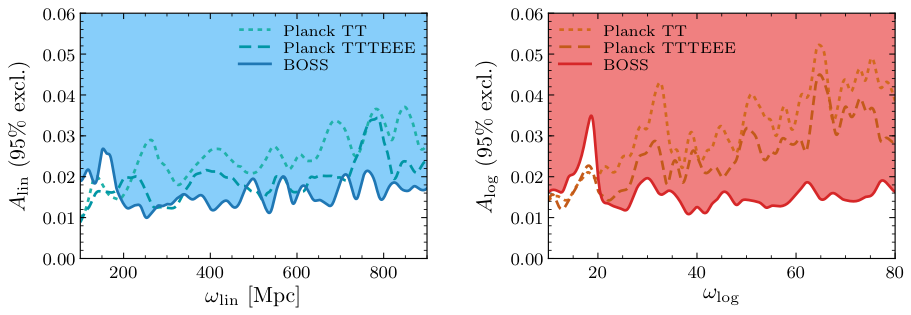

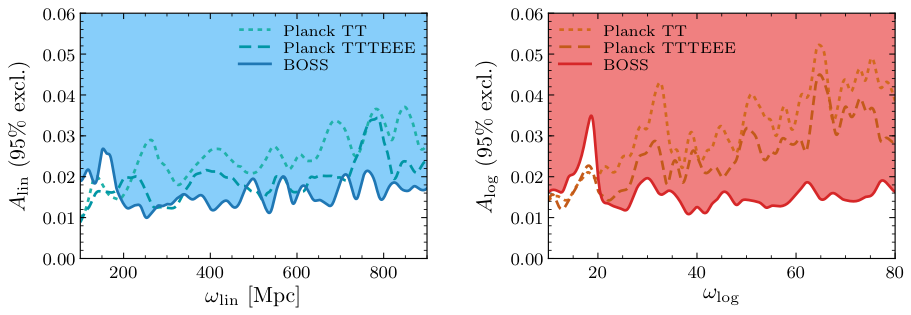

Primordial features as a probe of inflation

Some inflationary models imprint unique features in the early density field, which can still be detected with galaxy surveys today.

Axion monodromy models or models with

non-BunchDavies initial

conditions predict linear or logarithmic oscillations in the primordial power spectrum. The CMB has provided some constraints

on these inflationary models, but even current datasets like BOSS can provide competitive constraints at complementary wavelength

ranges.

Future survey experiments like

Euclid and DESI will be able to improve such constraints by a factor of 10,

providing new, exciting discovery opportunities. Current

constraints from the BOSS survey, compared to Planck for linear and logarithmic features are shown in the plot above (further reading:

Beutler et al. 2019).

Using deep convolutional neural networks to classify astronomical objects

The DESI survey is currently collecting photometric data which will be used for target

selection for the follow up spectroscopic

experiment. There will be about 40Tb of photometric data available at the end of the project. These images contain about 300

million galaxies and stars. I want to explore how machine learning, and in particular deep convolutional neural networks,

can be used to classify these objects, potentially improving the quasar and galaxy targeting for the DESI experiment. The enormous

size of this dataset also provides powerful statistics to constrain galaxy formation models.

This project will make use of the Google TensorFlow package, which will be

interfaced through python. This project allows to combine cutting edge machine learning techniques with cutting edge astronomical

research (further reading: http://legacysurvey.org; Kim & Brunner 2016).

Also, there is a machine learning project related to benty-fields, which I am happy to supervise. Have a look here for more details.

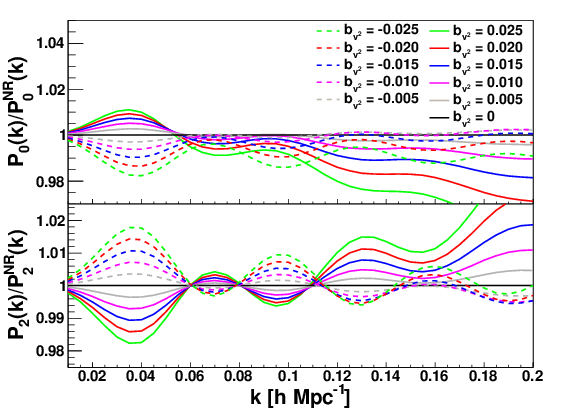

Measuring the neutrino mass using galaxy clustering

It is an amazing fact that we can use the clustering of galaxies to learn about the properties of some of the lightest particles in the Universe, neutrinos. Neutrinos produced during the Big Bang are still around and have typically a very large velocity. This large velocity prevents

neutrinos from contributing to the small scale clustering, unlike baryons and cold dark matter. This reduction in small scale

clustering is proportional to the mass of the neutrino particle. We can, therefore, measure the neutrino mass by studying the clustering of matter in

the Universe.

The big price is the detection of the sum of the neutrino masses, which is currently unknown. Several laboratory experiments try to measure

this parameter, but cosmological probes are more sensitive and should be able to measure it first. This would be a major

contribution of cosmology to the standard model of particle physics and could determine the mass hierarchy of neutrinos (further reading:

Lesgourgues & Pastor 2006; Beutler et al. 2014).

Higher order clustering of galaxies in the Universe

The clustering of galaxies can be used to study properties of the Universe. A different amount of dark energy in the Universe will lead to a different clustering

pattern. Therefore by statistically analyzing the matter distribution in the Universe we can learn about the

properties of dark energy. Similarly, we can learn about the age of the Universe, the amount of dark matter, the properties of neutrinos,

the nature of gravity and much more.

A statistically optimal approach to study the clustering of galaxies is the calculation of the so called N-point functions. The lowest-order N-point function is a standard tool in such studies, but the inclusion of higher order N-point functions has been proven difficult. Higher order statistics can help to constrain the early Universe through measurements of primordial non-Gaussianity.

It can also help to constrain redshift-space distortion and neutrino mass measurements.

I am interested in developing efficient estimators for the galaxy bispectrum (Fourier-transform of the 3-point function) and use them

for cosmological constraints. This project involves the development of statistically optimal estimators and to find computationally

efficient algorithms to calculate these estimators. Recently my collaborators and I developed a new bispectrum estimator (Sugiyama, Saito, Beutler & Seo 2018), which

compresses the available data more efficiently and allows for a self-consistent treatment of the survey geometry. Ultimately this

project will use datasets like BOSS,

eBOSS and eventually

Euclid and DESI

to constrain cosmological models (further reading:

Tellarini et al. 2016,

de Putter et al. 2018).

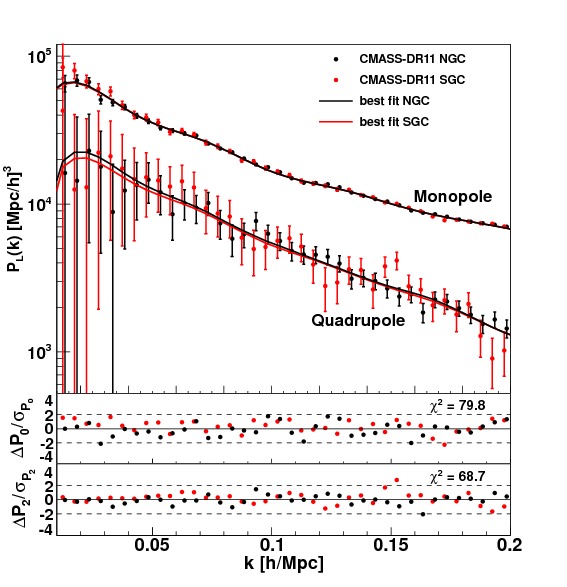

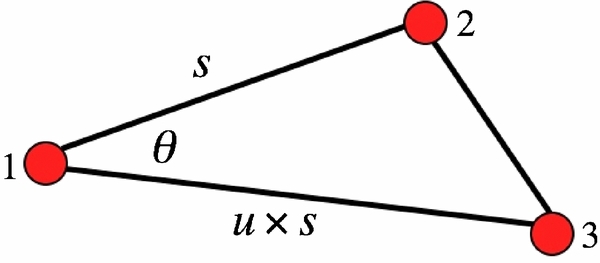

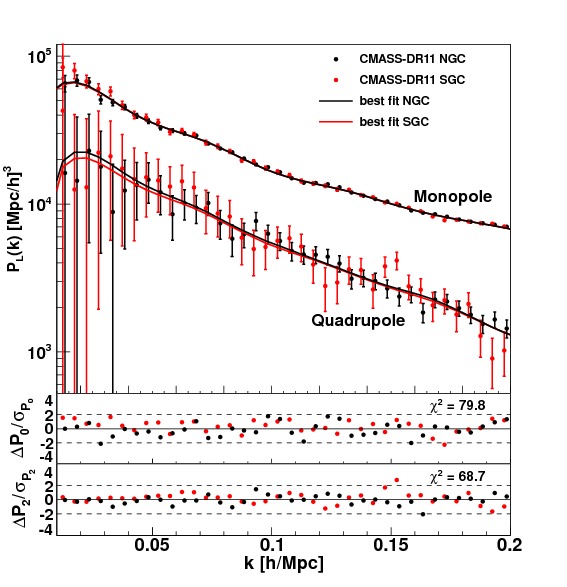

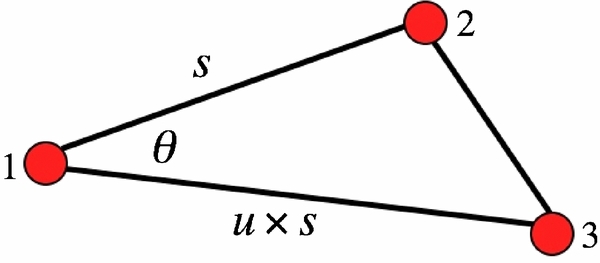

Redshift-space distortions as a probe of modified gravity and dark energy

The galaxies we observe with telescopes do not just trace the underlying matter distribution, but the underlying velocity field.

This allows us to measure distances, since galaxies which are further away from us recede faster from us, which is known as Hubble's law.

Beside the recession velocity, galaxies are also subject to the local velocity field, sourced by gravitational evolution.

These local velocities imprint a signal in the galaxy distribution, which allows a direct test of gravity theories.

One explanation for the accelerated late time expansion of the Universe (dark energy) could be a modification of General Relativity

on very large scales. Redshift-space distortions are a very interesting tool to test such theories (further reading: Kaiser 1987; Beutler et al. 2014; Perko, Senatore, Jennings & Wechsler 2016; Hand, Seljak, Beutler & Vlah 2017).

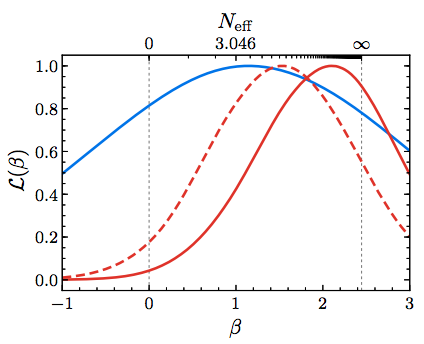

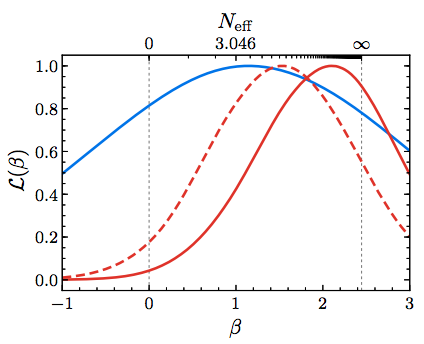

Detecting the cosmic neutrino background

The large-scale structure of the Universe is not just sensitive to the neutrino mass but also to the total number of such particles.

In particular we are sensitive to the fact that neutrinos decouple very early from all other matter (free-streaming).

Using the Baryon Acoustic Oscillation (BAO) scale we can constrain the number of free-streaming particles in the early Universe using

the standard ruler technique (see first project) or using the phase of the BAO (Baumann et al. 2018). Of all the particles in the standard model of particle physics, only neutrinos

would be able to free-stream in the early Universe, but it is possible that the Big Bang produced additional unknown

particles. The latest data from the Planck satellite

ruled out the existance of additional particles at the energy level of neutrinos (weak force) but it is absolutely possible that

there are additional particles at higher energies. Particles which decoupled at the QCD energy scale are still allowed

by current constraints. Future CMB and galaxy survey datasets will significantly

improve these measurements and will be able to discover or rule out any unknown dark radiation produced by the Big Bang

(further reading: Baumann, Green & Wallisch 2017; or have a look at this blog post).

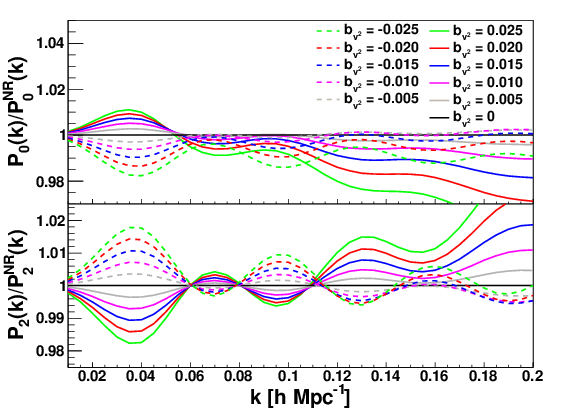

The baryon - dark matter relative velocity effect

The relative velocity between cold dark matter and baryons has long been neglected since it has been considered a small effect. In recent years

cosmological measurements have reached very high precision and systematic errors are a major concern for all cosmological observables.

The suppression of growth in baryon perturbations before decoupling is one source of the relative velocity between baryons and cold dark

matter. This effect is particularly interesting for Baryon Acoustic Oscillations, since it acts on the same scale. I study the relative velocity effect using

perturbation theory and observational data. The most recent constraints from the Baryon Oscillation Spectroscopic Survey (BOSS) have

only been able to set upper limits on this effect, but future surveys are potentially able to yield a detection (see Beutler et al. 2017). Studying this effect is

essential to avoid systematic biases in measurements of the Baryon Acoustic Oscillation scale, but it is also interesting given its

potential implications for galaxy formation models (further reading:

Tseliakhovich & Hirata 2010; Yoo, Dalal & Seljak 2011; Schmidt 2016; or have a look at this blog post).